Gabriel

Archer 1575–1609

9th

Great-Granduncle of E. David Arthur

Captain Gabriel Archer

Birth: 1575 Mountnessing, County

Essex, England

Death: 1609 Jamestown, Virginia

Father: John Archer

Mother: Eleanor Frewin

Brother: John Archer, Jr who is the Father of George Archer

Sr. (my 8th Great-Grandfather)

George Archer, Jr. - Son-in-law of Col. Abraham Wood

https://edavidarthur.tripod.com/AbrahamWood/AbrahamWood.htm

Gabriel Archer was one of the 5 captains in the 1607

expedition to settle Virginia. This expedition was sponsored by the Virginia

Company of London and Gabriel was an owner of company stock. After he died at

Jamestown ca.1609, his brother John Archer inherited his stock. This John

Archer lived and remained in England. John Archer's son, George Archer

(Gabriel's nephew), came to Virginia courtesy of Francis Eppes,

who evidently paid his passage and to whom he owed his "servant"

status. George Archer was the immigrant ancestor of many of the Chesterfield

County Virginia Archers.

He began his

Virginia journey as co-captain of the "Godspeed", and recorded the

settlers' first exploration of the James River in 1607 with Captain Christopher

Newport.

The first of this family in America was Gabriel Archer,

whose name accompanies that of Capt. John Smith on a monument at the head of

the oldest residential street in Richmond, Virginia. It is in a small park on

the James River, and commemorates their landing in 1607.

The name Archer is Norman-English, and claims descent from

Baron Archer, whose name is found in Battle Abbey on the Battle of Hastings.

Source: David Robertson

Gabriel arrived in America in 1607and helped found

Jamestown. He returned to England in 1608. Gabriel Archer arrived in America in

1607 with John Smith and others.

Gabriel Archer and others, including Captain John Smith,

George S. Percy, Edward Wingfield, and George Kendall, arrived on board the

three ships - Sarah Constant, Discovery and Goodspeed on 24 May 1606 and

founded Jamestown, Virginia.

He was among the first to be wounded by Indians while still

aboard the ship before disembarking.

"Archer's Hope" (now called College Creek), a

small cove and creek just south of Jamestown is named for him, as he hoped this

would be the hospitable place for settlement. It proved undesirable because the

water was too shallow for ships. (The Williamsburg Winery, with the Gabriel

Archer Tavern, is presently located on this site.)

Gabriel entered Gray's Inn as a student of law March 15,

1593.

He matriculated at Oxford University.

In 1602 he went with Bartholomew/Barnard Gosnold to New England and wrote an interesting account of

the discovery and naming of Cape Cod and Martha's Vineyard.

He was among the first to put foot on land at Cape Henry,

Virginia on April 26, 1607.

He was appointed Recorder of the Jamestown Colony. He

traveled with Newport from Jamestown on a voyage of discovery up the James

River.

Gabriel Archer maintained a high ranking in the company of

gentlemen that first came to settle in Virginia. Born in Essex c.1575, he

attended Cambridge and is considered to be Virginia's first lawyer (according

to Edward W. Haile).

Archer went home to England in 1608, returning to Virginia

in 1609, to take his place as Secretary to the Council. Most of what is known

about Gabriel Archer comes from the accounts of the various gentlemen who

traveled with him from England to the New World. These place him in positions

of plotting and scheming with Captains Martin, Ratcliff and others to remove

Captain Smith. Accounts of Archer ended during the "starving time" of

1609-1610, when it is assumed he perished with the other settlers. (Only 60 of

approximately 500 survived.)

Archer's Hope

"The twelfth day (May), we went back to our ships and

discovered a point of land called 'Archer's Hope,' which was sufficient with a

little labor to defend ourselves against any enemy; the soil was good and

fruitful with excellent good timber; there are also great store of vines in

bigness of a man's thigh, running up to the tops of the trees in great

abundance; we also did see many squirrels, conies, blackbirds with crimson

wings, and divers other fowls and birds of divers and sundry colors of crimson,

watchet (sky blue), yellow, green, murrey (purple red), and of divers other hues naturally

without any art using; we found store of turkey nests and many eggs. If it had

not been disliked because the ship could not ride near the shore, we had

settled there to all the colony's contentment." (Taken from the written

discourse of Master George Percy, 1606/1607)

In 1607, the Susan Constant, Discovery, and Godspeed

reached the shores of Virginia. After exploring several sites along the mouth

of the Chesapeake Bay, the colonists, fearing pirates and Spanish competition,

decided to explore further inland. Captain Gabriel Archer proposed they settle

on Archer’s Hope where the winery now stands.

Jamestown, because of its deeper off-shore waters allowing

close mooring for the ships, was chosen instead. It is not clear whether

Archer's Hope refers to the Captain's wish for placement of the settlement or

to an old English meaning of the word hope, "a small protected cove or

inlet." Archer's Hope is mentioned twelve years later in the first land

grant to the "Ancient Planters," as the nineteenth land grant of 100

acres acquired by John Johnson for an annual lease of two shillings. Later, the

property was mapped in 1781 by French Army cartographers disembarking on the

shores of the James River to join the armies of Rochambeau, Lafayette, and

George Washington. Source: The Williamsburg Winery website

2013 Jamestown excavation unearths four bodies — and a

mystery in a small box

JAMESTOWN, Va. — When his friends buried Capt. Gabriel

Archer here about 1609, they dug his grave inside a church, lowered his coffin

into the ground and placed a sealed silver box on the lid.

This English outpost was then a desperate place. The

“starving time,” they called it. Scores had died of hunger and disease.

Survivors were walking skeletons, besieged by Indians, and reduced to eating

snakes, dogs and one another.

The tiny, hexagonal box, etched with the letter “M,”

contained seven bone fragments and a small lead vial, and it probably was an

object of veneration, cherished as disaster closed in on the colony.

On Tuesday, more than 400 years after the mysterious box

was buried, Jamestown Rediscovery and the Smithsonian Institution announced

that archaeologists have found it, as well as the graves of Archer and three

other VIPs.

“It’s the most remarkable archaeology discovery of recent

years,” said James Horn, president of Jamestown Rediscovery, which made the

find. “It’s a huge deal.”

The discovery, announced during a morning news conference

at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History, deepens the portrait

of the first permanent English settlement in North America, established here in

1607.

It also raises intriguing questions about Jamestown’s first

residents.

Where did the silver box come from? Are the bones inside it

human, as they seem? If so, whose are they? And why was the box placed in

Archer’s grave?

Horn said in an interview before the announcement that the

box is a reliquary, a container for holy relics, such as the bones of a saint.

“It’s a sacred object of great significance,” he said.

Such containers have a long tradition in the Catholic

Church and predate the Protestant Reformation. So the appearance of one in

post-Reformation Jamestown is mystifying.

Did it belonged to Archer, whose Catholic parents had been

“outlawed” for their faith in England? Or to the fledgling Anglican Church, as

a holdover from Catholicism?

“More research, more work” is required, Horn said.

“Frankly, we need more help with interpreting this.”

Putting pieces together

On a chilly November day in 2013, archaeologist Jamie May

reached into the dirt of grave “C,” in what had been the chancel of the church,

built inside the walls of James Fort in 1608.

With the thumb and forefinger of her left hand she gripped

the little box, and with the other hand gently worked it free with a small

wooden tool. As she lifted it out, Director of Archaeology William M. Kelso

asked, “Does it feel hollow?”

“Yeah,” she said. “And it feels like there’s something in

it.”

It had been three years since the Jamestown archaeologists

had come across the huge post holes that outlined the long-vanished church,

with the side-by-side graves inside. (The church, itself a historic find, was

legendary as the place where the Indian princess Pocahontas married Englishman

John Rolfe.)

Now, after months of research and preparation, the

Jamestown team, along with anthropologists from the Smithsonian, were

excavating the burial sites.

Grave “A” contained the skeleton of the Rev. Robert Hunt,

who was about 39 and was the first Anglican minister in the country, experts

concluded from records and studies of the remains.

A devout peacemaker from Hampshire, in southern England, he

had brought his library with him when he came over in 1607 with the first

colonists.

He may have left England, in part, because he suspected his

wife was having an affair, according to records reviewed for the Smithsonian by

Ancestry.com.

But his books were destroyed in a fire that gutted the

compound in 1608, and he died the same year.

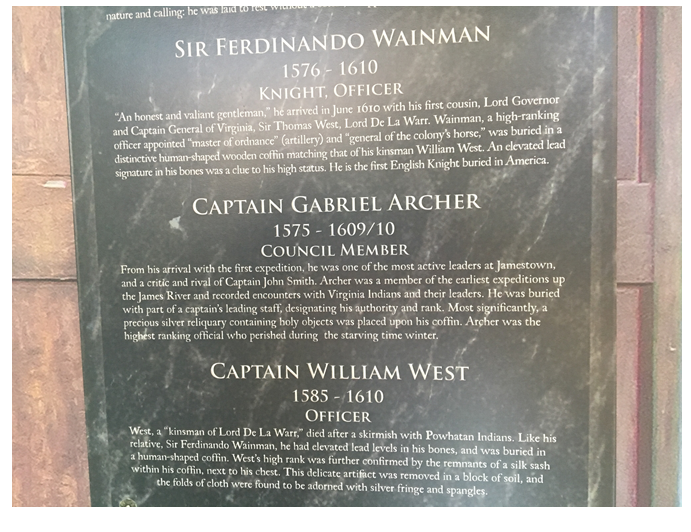

Grave “B” held the skeleton of Sir Ferdinando Wainman, who was about 34, “an honest and valiant

gentleman,” wrote a friend. He died in 1610 and was buried in a fancy wooden

coffin.

Although the coffin had disintegrated, its unusual shape,

which included a “head box,” was determined by plotting the outline of the

nails that survived.

The “anthropoid” coffin, which slightly resembles those of

ancient Egypt, is “one of the few ever found in English America,” Horn said.

Wainman’s bones

contained high levels of lead, indicating that he probably dined using pewter

plates and goblets, a sign of high status, Horn said.

Grave “C” contained the remains of Archer, who was about

34.

He stood only 5-foot-5 and was among the leading men who

arrived in 1607. He was a lawyer and scribe, and his hands had been wounded in

a skirmish with Indians.

Archer had terrible teeth, with 14 cavities and two

abscesses, said Douglas Owsley, the lead Smithsonian anthropologist, who

studied the remains in the field and at the Natural History museum.

Archer was buried in a coffin of white oak, and the silver

box was found on top, near his lower left leg.

Grave “D” bore the remains of Capt. William West, who was

about 24 and had been killed fighting Indians in 1610 near where Richmond is

today. He also was buried in an anthropoid coffin, made by the same carpenter

who made Wainman’s, Owsley said.

Remnants of a military sash, fringed with silver thread and

tiny metal baubles, were found with his bones.

Owsley said in an interview this month that he does not

know how the men died, but that “they died fast.”

The graves — inside the chancel, or altar area, of the

timber and mud church — indicated that the occupants were esteemed members of

the community.

“It would have been only the prominent who were buried

there,” Horn said in an interview this month.

“What we’re learning about are four of the first founders

of English America,” he said. “There’s no other way to put it.”

‘We are starved’

In the spring of 1610, three years after the first

settlement, two English ships loaded with settlers made their way to Jamestown,

filled with anticipation.

What they found was horrifying.

The fort’s palisade had been torn down and the church was

crumbling, according to Horn’s history of Jamestown.

It “looked rather as the ruins of some ancient

[fortification] than that any people living might . . .

now inhabit it,” wrote Sir Thomas Gates, one of the newcomers.

Of the 300 or so colonists who had been there the previous

fall, only about 60 emaciated survivors remained. They were “lamentable to behowlde,” Gates wrote, “cryeinge

owtt, ‘we are starved. We are starved.’ ”

It was during the previous six months, which had been the worst, that Archer probably died.

“Having fed upon

horses and other beasts as long as they lasted, we were glad to make shift with

vermin, as [well as] dogs, cats, rats and mice,” George Percy, a Jamestown leader,

wrote of that period.

“Famine beginning to look ghastly and pale in every face . . . nothing was spared to maintain life

and [settlers did] those things which seem incredible,” he wrote later.

One of those things was cannibalism. In 2012, Jamestown

archaeologists found the skull of a girl that bore cut marks, as though it had

been carved. Smithsonian anthropologists later determined that she was about

14.

Other people dug up corpses for food, Percy wrote, or went

mad and ran off into the woods to be killed by Indians.

There was “a lecture of misery in our people’s faces,”

Percy wrote.

Mystery in a small box

On Jan. 22, in the Natural History museum’s electron

microscopy lab, Scott Whittaker focused his powerful microscope on the silver

box, the size of a salt shaker, illuminated under the lens.

As Owsley and a delegation from Jamestown watched,

Whittaker zoomed in on the letter etched on the lid.

Was it an M or a W? For about three hours, Whittaker and

the others studied the letter, and the construction of the box.

They were able to figure out the sequence in which the

lines were cut, deduced that the carver was probably right-handed, and finally

determined that the letter was an M.

But what did it mean? Archer’s mother’s name was Mary. He

came from a town called Mountnessing, outside London.

“We don’t know what the link is,” Owsley said.

It was one of many questions presented by the 400-year-old

box and its contents.

Studies and scans showed that the box was made of

non-English silver, and originated in continental Europe many decades before it

reached Jamestown.

Horn said he believed it was a sacred, public reliquary, as

opposed to a private item, because it contained so many pieces of bone.

“A private reliquary would be like a locket, or a small

crucifix, with a tiny fragment of bone,” he said. This probably was for public

display and devotion.

Reliquaries usually are associated with Catholics, he said,

adding, “What’s that mean for Gabriel Archer?”

Archer was not known to be Catholic. But his parents in

England had been “recusants,” Catholics who refused to attend the Protestant

Anglican Church, as required by law after the Reformation.

Horn wondered: Was Archer a leader of a secret Catholic

cell? In 1607, George Kendall, a member of the settlement’s governing council,

was executed as a Catholic spy, according to Jamestown Rediscovery, and Horn

said Tuesday, “I’m beginning to lean more to the Catholic conspiracy.”

But another theory is that the reliquary belonged to

Jamestown’s fledgling Anglican Church. Even though reliquaries were “relics of

the old religion,” Horn said, some were retained for use in the early English

Protestant Church.

If that’s the case, the reliquary was the “heart and soul”

of the English church in the new world. And its burial with Archer could be a

last desperate act to save it from desecration by Indians, with whom the

settlers had been at war, he said.

Experts have viewed the contents via X-rays and high-tech

scans. The box has not been opened.

The bones, about the length of a toothpick, appear to be

human, said Kari Bruwelheide, a forensic

anthropologist at the Smithsonian.

“It’s very difficult to say with 100 percent confidence if

something is human or not, if you don’t have the real object in your hand,” she

said.

But Jamestown has plastic models of the bones, made via 3-D

“printing,” and they appear to be consistent with human bones, possibly limb

bones, Bruwelheide said.

The box also contained a tiny lead vial, or ampulla, that

had been twisted open and was in two pieces. Such vials were sacred souvenirs

among ancient pilgrims, and they might have contained oil, water or blood, said

Jamestown curator Merry A. Outlaw.

It’s not clear when or why it was opened, or when or why it

was sealed inside the reliquary.

Kelso, the head archaeologist, said that for now the bones

will be kept in a vault at the Jamestown complex, where they can be available

for future study.

He said in an e-mail that there are plans to build a

memorial garden and mausoleum to hold all the remains recovered at Jamestown

over the years.

The reliquary will go on periodic display, he said.

There are no plans to open it.

“It would likely damage the box,” he said. “And while I am

far from a staunchly religious person . . .

it seems to me that keeping it closed is somehow the right, respectful thing to

do.”

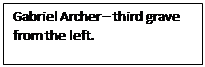

Captain

Gabriel Archer Plaque at Historical Jamestowne

Christopher

Newport’s exploration of the James River

When the English colonists were first exploring Virginia,

they quickly explored up the rivers as far as their ships could float. In 1607,

Christopher Newport sailed up the James River to the location of what is now

Richmond, before returning to England and reporting on his success at

delivering 104 colonists to a new settlement called Jamestown. Gabriel Archer

accompanied Newport and is believed to have taken notes for Newport's report

along the trip to the James River Fall line, which described the Indian peoples

they encountered and the promise of the land.

Newport discovered rapids that blocked further travel. The

river which the colonists named after James I dropped over 100 feet in

elevation, exposing granite bedrock and boulders which kept Newport from

sailing further west.

It was Newport's experience as well as his reputation which

led to his hiring in 1606 by the Virginia Company of London. The company had

been granted a proprietorship to establish a settlement in the Virginia Colony

by King James I. Newport took charge of the ship Susan Constant, and on the

1606–1607 voyage, she carried 71 colonists, all male, one of whom was John

Smith. As soon as land was in sight, sealed orders from the Virginia Company

were opened which named Newport as a member of the governing Council of the

Colony. On 29 April, Newport erected a cross at the mouth of the bay, at a

place they named Cape Henry, to claim the land for the Crown. In the following

days, the ships ventured inland upstream along the James River seeking a

suitable location for their settlement as defined in their orders. Newport

(accompanied by Smith) then explored the Powhatan Flu (River) up to Richmond

(the Powhatan Flu would soon be called the James River).

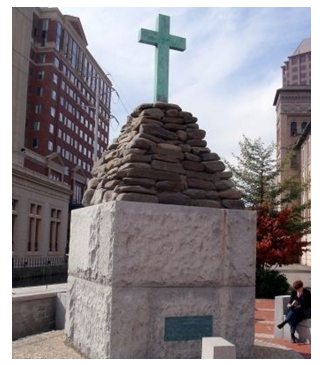

There is a monument near the Fall Line to mark the spot

near where Christopher Newport and John Smith landed on May 24, 1607. They set up a wooden cross on one of the

small islands in the James River and inscribed it with the words Jacobus Rex,

1607 (“King James, 1607”). The actual

cross has long since rotted away, so a bronze cross was used for this memorial,

and it stands on top of a pyramid of James River granite. The monument has actually been moved two

times. When it was built in 1907 it was

located in Gamble’s Hill Park, overlooking the river below; then in 1983 it was

moved to Shockoe Slip, closer to the river; finally

in 2003 it was moved to its present location along the canal walk, even closer

to the landing spot of Christopher Newport.

Christopher Newport Monument

https://www.hmdb.org/m.asp?m=23818

Christopher Newport Monument Marker image. Photographed By

Bernard Fisher, October 25, 2009

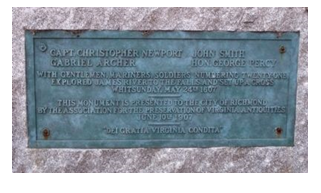

Christopher Newport Monument Marker

Inscription.

Capt. Christopher

Newport

John

Smith

Gabriel

Archer

Hon.

George Percy

With gentlemen, mariners, soldiers numbering twenty-one

explored James River to the falls, and set up a cross

Whitsunday, May 24th 1607

This monument is presented to the City of Richmond by the

Association for the Preservation of Virginia Antiquities

June 10th 1907

“Dei Gratia Virginia Condita”

Erected 1907 by Association for the Preservation of

Virginia Antiquities.

Location. 37° 32.034′ N,

77° 26.184′ W. Marker is in Richmond, Virginia. Marker can be reached

from the intersection of South 12th Street and East Byrd Street. This monument

is on the Richmond Riverfront Canal Walk.

Marker is in this post office area: Richmond VA 23219, United States of

America.

Download a pdf file of this page at

https://edavidarthur.tripod.com/GabrielArcher/GabrielArcher1575.pdf