Thomas

E. Harris 1585 - 1654 – “Ancient Planter”

My

9th Great-Grandfather –by David Arthur

The account below contains information about Thomas, his

son William, and Francis Eppes II. William and

Francis are both my 8th Great-Grandfathers who were neighbors.

“Ancient

Planters” - http://www.ancientplanters.org/

The term "Ancient Planter" is applied to those

persons who arrived in Virginia before 1616, remained for a period of three

years, paid their passage, and survived the massacre of 1622. They received the

first patents of land in the new world as authorized by Sir Thomas Dale in 1618

for their personal adventure.

Lines

of Decent

William Harris > Eliz. Ann Harris > Margery Archer

> Ann Cousins > John Overby > Robert “Robin”

Overby > William Epps Overby

> David Overby > James Overby

> Bertha Overby > David Arthur.

Francis Eppes II > William Eppes > John Eppes > John Eppes, Jr. > Charlotte Eppes

> Robert “Robin” Overby > William Epps Overby > David Overby >

James Overby > Bertha Overby

> David Arthur.

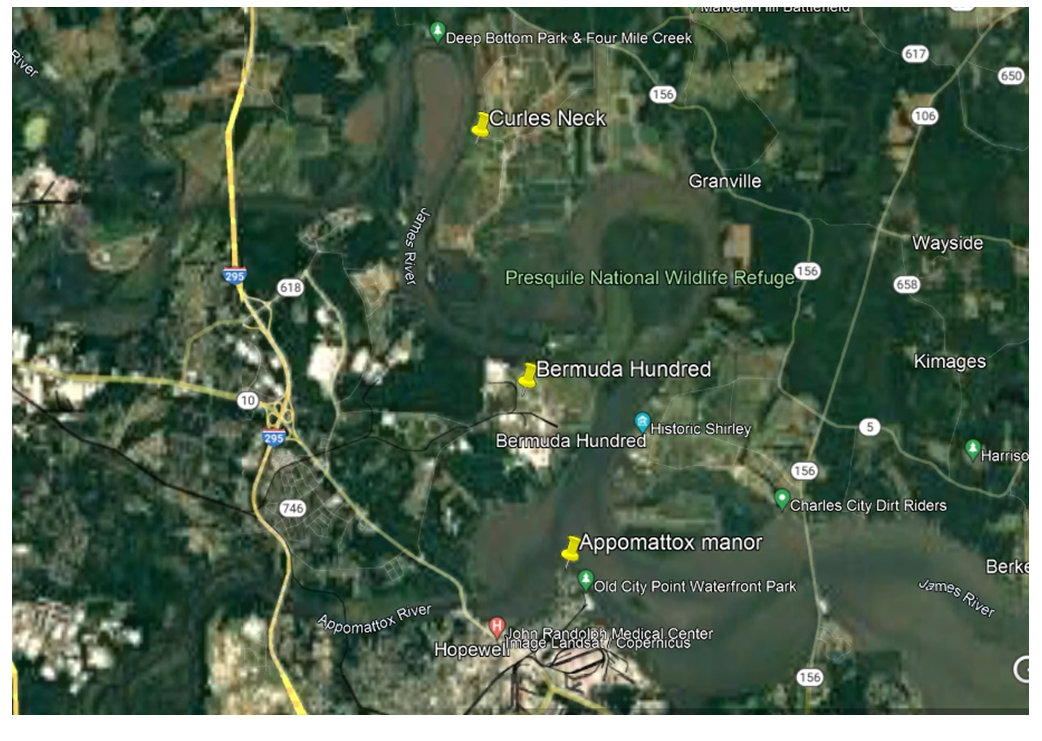

Map of

the Area

William

Harris – Account of his father Thomas Harris - A

fictitious “document” presented and prepared based on facts.

By - Dan Mouer

This is like a biographical novel with the pretense that

the author is transcribing a historical document. The assignment Mary Praetzellis gave to those who participated in the

“Archaeologists as Storytellers” session at the 1997 SHA meeting was to tell a

story about a person, a family, or a place using “data” from an archaeological

excavation as source material.

Curls, Plantation, Henrico County, Virginia

https://danmouer.blog/tag/curles-plantation/

A True Story of the Ancient Planter and Adventurer in

Virginia, Captaine Thomas Harris, Gent.,

as Related by his Second Sonne

Published as “Archaeology Through Narrative: Captaine Thomas Harris, Gent,” in Historical Archaeology,

Volume 32, Spring 1998. Tucson: Society for Historical Archaeology.

The day before he was to die at the hands of Chickahominy

Indians in the Summer of 1678, Major William Harris

visited the widow of the rebel General Bacon at Curles,

once his father’s plantation and the place of William’s childhood. The ancient

seat was now nearly destroyed by the depredations of the Governor’s men in

retaliation for the late uprising, but the home he best remembered–his father’s

greatest pride–had been levelled by fire twenty years earlier. More than a year

had passed of her widowhood, but Elizabeth Bacon, with her Black, Indian and

German servants lived on in the mud and ashes of the Curles

estate. His recollections jarred by the visit, and by a dread premonition of

his coming expedition, Major Harris sat in the Indian’s house and told the boy

servants his father’s life story, which comes to us in the form of a petition

from Harris to the acting governor of Virginia. I have taken some care to

transcribe the document using modern usages and spelling only where needed for

clarity. I have likewise spelled out some words abbreviated in the original,

and these instances are marked with brackets ({}). In a very few instances I

have extrapolated a likely word or phrase which was illegible in the original,

and these are denoted by square brackets ([]).

THE PETITION OF WILLIAM HARRIS

To His Excellency The Hon’ble Acting Governor and High

{Commissioner} of His {Majesty’s Plantation} of Virginia, Colonel William Jeffreys from your most obdnt

Servant, Will: Harris, Major and Deputy of the Combined Militias of Henrico and

Charles City pray permit me through whatever intermediary this comes to you to

petition your exlcy on behalf of an Indian Boy named

Tom, of 18 yrs of age, presently a Servant in the

estate of the former Rebel and Scourge of our country, Nat’l Bacon, Jr. now

deceased. This Boy dwells at present with the widowed relict of the sd rebel at his late plantation, known as Curles, in the Coty of Henrico, said estate {presently} in

the sizen of your exlcy on

behalf of his majesty due to the treason of said Bacon. This Boy is remarkable

in these parts even were he Christian, yet he is a

Heathen of the Pamunkeys, a nephew, I believe, of the

noble Queen of that tribe with whom we have at long last made of late a peace.

The boy is well learned in our ways and language and he is

as capable a scribe as any clark

or barrister. {With proper nourishment} of his soul, and some further tutoring

in Classics, the boy would serve well as an {ambassador} of his people. He will

without doubt bring more boys from the Indians to live among us, to hunt and

plant, and to take instrucion in true religion and be

baptised, {thereafter} to become fine Citizens of

this Country. Mrs. Bacon will soon leave here to attend on Mr. Jarvis, to whom

she has become betrothd, at his {plantation} in the

lower parts of Nansemond. Unless you make some dispensacion

for this Boy and his young brother, a Boy about 12 years named Nat’l, they will

be sold as slaves, and of late many Indians have been sold to the Carolina

Savages who use them poorly. And t’were in my estimacion a strange Oeconomie

where we send our Indian’s boys to them and they send their captured Boys to

us, and an injustice to Ourselves to so {jeopardize} the peace by sending forth

such a one as this who could only by resentment turn his learning to our detrimnt through [treachery.]

I have only met this Boy to=night. I came to lodge at Curles in the hospitality of Mrs

Bacon due to a violent Gust and Torrent that has swoln

all the creeks of the upper parts of James His River. The night fell early and

I feared my horse would mis=step. Knowing the road to

Curles was at hand I entered this anciente

plantacn, once my father’s own, and the Home of my

youth. After a meager meal with the rebel’s Widow (and her having no man at

home other than a Dutch servant), she directed me to a quarters house where I

should lie the night with her Indian Servants, she having seven of these as

well five Negroes from Africa and Brazil. As I entered the small wooden House

this young Man arose respectfully and, in the Indian manner, he made no talk,

nor did I, but he took a Pipe and {Pouch} from a small trap in the floor filled

it with fine sweet=scented tobacco, brought the Ember to it and passed it me.

Nor he nor I spoke a Word til all the smoke was extinguisht from his Pipe. Then he spoke first saying he

knew me, and welcomed I should take his Bed and bolster.

He asked if I had fought against his great grandfather, the

old divil King Opechancanough

wherein I told him I was then too young, but that my father had done so,

{notwithstanding} I had seen the great Chief before he was murthered

in James City. This boy then asked where my father’s House was, and I near was

brought to tears, for it had once stood not a stone’s throw from the servant

hut where we spoke and these words are written. He asked I tell him about my

Father which I did to pass the time and to educate these boys–though I know not

the younger understood a word–about the history of our time in this Country. As

I spoke he wrote near every word, and this, his writing of my words, I have

placed with this letter that you may read it. I do not presume to entertain you

with my story=telling as I have done this night to educate these Heathens, but

only to shew the Cleverness of this servant who I pray you to save from slavery

so that he might serve his people and ours in an adventure of a peaceful

Communion. What follows are my words true as spake to

the Indian lads.

THOMAS HARRIS HIS STORY

My father, Captaine Thomas Harris

come hither aboard the Prosperus from England, a land

I know not, in the year of sixteen hundred and eleven to serve with Sir Thomas

Dale his Government. He told me in my youth that he had no estate in England

and that his only hope was as a soldier of fortune in the plantacions

or as a soldier to fodder the Canons in Holland. He chose then to be a Planter

rather than himself to be planted in the ground at so young an age, and he came

to decide between signing for Ireland or Virginia, and he swore he would not go

among the savage Irish or ever live in a Hovel of mud and sticks, for that is

how he dreamed of the Irish plantation. And he reasoned that should he have to

die at the hands of Salvages, better it would be of a heathen Indian than an

uncivilized Christian who knows no King, but only a cardinal Bishop. And so he

purchased his stock as an Adventurer in the Company and came hither after a

terrible voyage wch near killed all in a Tempest or Hurricano.

The year he came to this plantation twas

the Starving Time for English and Indian alike, and there was no house in

useful repair in James City, and the walls of the Ffort

were nearly tumbled in the dust. Governor Dale made mends to James Fforte and then, seeking a safer and more healthful seat up

the main River, he took near all the Companie to

build the City of Henrico, and having barely laid the plan of the towne and paled it in he took them all again to build a

city called the New Bermudas, wherein he commissioned

my father {Lieutenant} of Digges His Hundred in that City. Here my father and

my mother came to live in an old Indian house long since abandoned, blackened

by smoke, a Hovel of sticks, but at least not an Irish Hovel. At the end of the

first year he builded him the House in which I was

born at the foot of this neck of land along the main river. The House had one

room, no windows and a chimney of sticks plastered with mud. Here we lived when

Opechancanough and all the Indians rose against us

and slaughtered near 400 in one day of 1622. In my father’s charge three were

lost to the Indian treachery, and that House was burned to the Ground. For many

years we lived as tenants on the lands of others, in one of the fortified

settlements. We had another small wood House to ourselves and our servants, but

the {Tobacco} we made on a landlord’s field, and it were no Benefit to us. The

year 1630 the Governor released us from the Indian-imposed bondage to return to

our ruined {plantations} and tenancies and we come back then to Curles Neck where, finally, my Father said we should have a

proper English house, near twenty years after he come to this country.

My Mother had died and now with a new wife my Father and

Brother and I began to build the finest House in Henrico wch

was the among the first shires ands courts of the

country. We labored terribly in the Summer of that

year to dig a Cellar 18 feet by 24 feet and full 5 feet below the earth but

rising eight to the plaistered silling

overhead. On the side walls we erected stout posts, nogged

between with bricks fired by the house, and on the chimney wall we builded only of brick. The House raised a full room and a

garret above the lowroom Cellar, where stood the

Kitchen which served also as a Brewhouse, Buttery,

and Bakehouse as well our Magazine and Armory. The

house was covered with cypress shingles and on one end rose a [massive brick

chimney,] the finest of its kind in the upper parts. Nestled against the

hearth, half within and half without the house, was a large stone oven for my

new mother to bake fine bread for all those of the {neighborhood} who would

answer the perfume of its baking. This fine Hall, my father would say, was no

Irish Hovel.

The Greate Room was plaistered of mud and lime and washed with ochre, and the

walls were hung heavy with French clothes to keep the warmth of the hearths

within. My new mother would cook on the great hearth of the lowroom

with the help of my sister. We had then but two servants who worked the fields,

made and mended all our tools. as well serviced our Meate, Meale and Beer within the

hall. Mother, father, sister, brother and I all stooped over the hoe in the

fields beside the servants to bring in the crop each year and to plant the next,

except when my father was about his Business of soldiering, for he was above

all, before a Farmer or a Father, a Soldier. His great pride, beside his brick

house, was his rank of Captaine which they

{commissioned} him at the time I speak of. I remember how, as a youth, it

struck me with great dread to see him transformed in his armor gorget and tassets, a great steel

helm on his head, a broadsword in his sash and rapier to hand, his legs and

feet bound in Indian clothes and moccasins of coarse deerskin.

We lived well in that single Hall, low room and Garett for

many years, and we builded more buildings, in the

manner of the co’try, in our yarde.

A tobacco house was the first, and then a small barn for the Cattle, a Granary

and a dovecote. About the year 1640, my father resolved to enlarge the house.

Another year we dug a long passage to serve as a Buttery beside and beyond the

great hearth and opened it to another room as large as the Lowroom

below the hall. Above ground were new chambers for he

and my mother, one for my brother and I, and another for our Sister. In the gartt dwelt a maidserv’t from

France and a Negro girl, not a slave, for my father would have no truck with

the selling of flesh into perpetual servitude. When her time was passed, and

she had been brought to the Church, she married a baptized Indian and they

raised their plantacion on fifty acres a Gifte from my father.

And we builded this little wood

house wherein we now huddle as this be spoke and

written. Here lived the men and boy servants. I befriended one Indian named

Dick. He was my age and he made smoking pipes, beautifully cut out and

polished, decorated with Deer and the compass=rose. He made Pipes for all our

neighborhood. for men and women, some with their

Ciphers emblazoned in fine dentacions made by the artfull cut of a great shark’s tooth. He would roll out claye dug from the white Marl in the riverbank into tubes

and bury it for many days to season. To this he would add small measure of

quicklime. He burned them in the bread oven, and Mother–for I came to know her

as my mother– was much put off until he gave her pipes with her own cipher,

which she showed to all, smoking proudly with great billows at the Court or

Churchyard.

In the year 1644, the old King of Pamunkey,

Opechanough, raised another warre

against us. That day near 700 men women and children were delivered by sauvages to their maker’s judgment. The old Indian was

blind and more than 100 years old, and he was soon captured. I can remember

well the militia with my father at its Head brought him before the parade at

Henrico for all to see. It was no more than a few weeks after he was imprisnd in James Cittie that a

knavish rogue among the guard shot the anciente enemie in the Back, ending his fearful reign. Though Pamunkey served the work of the divil,

he knew no better, for he had not been instructed in the ways of our Lord; it

were a treachery worthy of the Salvage himself to have been murthered

so infamously.

They burned three plantacions in

these partes and killed nearly fourscore in Henrico,

but by God’s will, we were saved and our houses were unmolested. But then the

government resolved to stop the fearsome ravages once and for all, and we had a

long revenge upon yr people. I saw my father very

little for nearly two yeares as he led rangers

against the Appomattox, the Arrahatox, the Weyanokes, and the Manahoax. He

was busy too in the work of building new fortes at the Falls

and at {Chickahominy,} and commaunding them and their

garrisons. My brother being gonne

from the country for his learning, the management of this plantation fell to

me.

In the year 1654, in the 69th year of his Life, my Father

fell ill of the Ague and Fever. Of all he was the most seasoned of the ancient plaunters, yet the agues laid even him low. In those

evenings of his last days we would talk when the fever permitted. He told me

again his stories of coming hither, and how glad he was he had done so. He was

never a rich man, though our lives were {commodious} and we wanted for naught.

I had already builded my own house across the neck in

Charles City, but I never failed to think of Curles

as my home. He reminded me in his dying of what to him was important: that he

hoped he had pleased God and served his King and his fellow men: that he had

provided some small portion of an Estate for me and my brother and a Dowrie to secure my Sister an honorable husband: And he had

lived to see the plantation of Virginia survive, even flourish: not the home of

dandies the likes of which inhabit the Isle of Barbados, but rather as a place

where a man’s hands with Will and Fortune and Blessing could raise a living.

And he gestured weakly to the brick walls surrounding us, and said

“At least I did not die in a Netherlandish Myre or an Irish Hovel.”

OUR COUNTRY SPOIL’D

This your exllncy can see is the scribework of a talented young man. It breaks my heart to

see this plantacion, long since deprived of my

Father’s brick House by the act of God and the Neglect of Tenants, now ruined

further by the rebellion of Bacon and the retribution of our former govnr on his estates. The neighbors hereabouts daily

plunder this place and the Widow is helpless to defend it. The destruction and

thievery has so far been of the Crop and the buildings and their furnishings:

but soon they must spoil as well the cattle and servants for these are nearly

all of value that remain on the plantacn, save the

bricks from Mrs. Bacon’s own house and many timbers yet standing of the Rebel’s

great Ffort. For this reason I beseech you take this

Indian boy as your servant and godson, have him instructed in Faith and in the artes he might learn of a cultured Tutor. He, or someone

like him, may yet serve as the emissary to bring forever a lasting peaceful co=habitacion between the Indians and ourselves.

I would deliver this request and my Compliments in person

save I am to muster our county troop on the Morrow at Henrico Court to ride out

with Col. Eppes to the plantation of Rowland Pace

where several Indians have of late been marauding and it is reported they have stole a Pig and killed some chickens. These sauvages tolerate not the encroaching upon their champion

and meadows by the Planters in these parts who have late drained the marishes wherein the Indians are used to hunt. Nor do our

own Citizens take lightly theft of Swine whereon so many of the desperate ones

might feed a familie for a season or two. I would it

were not too late to avoid the letting of more human bloode.

God protect our country and God save the King.

yr most

humble etc.

(signed) Wm Harris

Given at Curles this day, 23rd Augst 1678

Telling

Captain Harris’s Story

Also from - https://danmouer.blog/tag/curles-plantation/

The assignment Mary Praetzellis

gave to those who participated in the “Archaeologists as Storytellers” session

at the 1997 SHA meeting was to tell a story about a person, a family, or a

place using “data” from an archaeological excavation as source material.

Discussion of archival or archaeological research was not to impose itself upon

the story. When constrained by the “rules” of narrative (and, in the case of

the live delivery at a conference, the rules of performance), I found, not

surprisingly, that competence in archaeology’s language and styles is no

guarantee one can be a decent story-teller in the strict sense. But the

experiment was instructive. In seeking a “voice” and a “face” to present the

story, I realized how little we know of language, costume, gesture, or other

aspects of daily social life on late 17th-century Virginia’s frontier. It made

the detailed groundedness of archaeological insight

seem, somehow, all the more important.

From the beginning, even before choosing a character or

plot, I knew I wanted to set my story at Curles

Plantation, a site I have worked on annually since 1984 (Figures 1 and 2). The Curles Plantation Site, in Henrico County, Virginia, was

settled about 1630, although earlier colonial settlement as part of Digges’s

Hundred is suggested by documents but not yet confirmed by archaeology. Thomas

Harris lived at Curles until his death in the middle

of the century, after which the plantation became a tenanted quarter of

merchant Thomas Ballard. In 1674, Ballard sold the plantation to Nathaniel

Bacon, Jr. who, in the three years he resided in Virginia (the last three of

his life) led a war with the Indians and a revolution against the colonial

government. By the time the dust settled, a long-time governor had been

unseated, colonial laws had been rewritten, and the local Native American

societies had been reduced to subjugation to English and Virginian authority.

The plantation was seized in 1677 by Bacon’s nemesis, Governor William

Berkeley, and it remained abandoned and wasted as a government holding until

1699. For the next century, Curles enjoyed a rebirth

and flourished as the seat of one of the most powerful families in Virginia.

The plantation entered a long period of decline beginning about 1810, and the

last of the remaining buildings were dismantled by Federal troops during the

Peninsula Campaign of 1862.

With assistance from a grant from the Virginia Historic

Landmarks Commission, I located and surveyed the site of the manor house

complex in 1984. Each year since then my students and I have conducted

excavations at Curles through the summer Field

Archaeology program at Virginia Commonwealth University. The Curles project is “unfunded” in any traditional sense; the

hard work (and ample tuition) of students has been the main source of

sponsorship. Enormous support has been offered by VCU’s Archaeological Research

Center (VCU-ARC), which has provided much staff assistance and virtually all of

the field and laboratory supplies needed for this enormous, on-going project.

We have periodically had generous assistance in the field from the owner of Curles Neck Farm, Mr. Richard Watkins, as well as from

Virginia Power Company and TARMAC, an international construction-materials

firm.

The first couple of years of full-scale excavation work

were dedicated to digging the 18th-century Randolph mansion and some associated

structures and features. In 1987 we discovered the small brick house Nathaniel

Bacon had constructed at Curles in 1674. We excavated

the house in 1988, and, the following year, we began to uncover the remains of

what appears to have been a huge fortification complex Bacon had constructed

around his home. By 1990, while excavating the 18th-century plantation kitchen,

we had stumbled upon the extensive remains of the Thomas Harris house. These four

structures–the Randolph kitchen, the two 17th-century houses, and Bacon’s

fort–have taken most of the efforts of the field school over the past decade,

although we have also excavated 18th-century gardens, 18th-century slave

quarters, a 17th-century brick clamp, and an assortment of drains, ditches,

wells, and other typical (and some not-so-typical) plantation features.

Over the years a great many students have undertaken

independent-study projects and internships that have contributed extensive

documentation about the site’s history, as well as bringing order to the vast

collections. While my debts are too many to mention, I must take special notice

of the tremendous contributions to this project by Beverly Binns,

VCU-ARC’s Laboratory Director and the field director at Curles

for most of recent history. I also want to acknowledge the tremendous trove of

documentary source material recovered from around the world and transcribed by

Katherine Harbury during her years as staff historian

at the Center.

While I have presented findings from Curles

regularly in papers delivered at local, regional and national meetings (Mouer 1993b; 1992a; 1991b, c; 1990a, b; 1989a, b; 1988b;

1987; 1985; Mouer, Wooley and Gleach

1986), little has been published, largely because it is an on-going project.

Articles about Bacon’s house at Curles have appeared

in Archaeology (Mouer 1991a) and in the Henrico

County Historical Magazine (Mouer 1988a), and I have

included chapters related to the Harris, Bacon and Randolph occupations at Curles in my forthcoming book for Plenum (Mouer 1998).

My views of the 17th century in the upper reaches of the

tidal parts of the James have also been influenced by my work (with Douglas McLearen) over three seasons of excavation at a complex of

sites on Jordan’s Point. These represented the fortified master compound and

some tenancies associated with the early-17th-century settlement known as

Jordan’s Journey (Mouer and McLearen

1991, 1992; McLearen and Mouer

1993, 1994; Mouer 1994). I have also researched the

17th-century history of the Fall-Line area for my projects at Rocketts (Mouer 1992, 1993c) and

Falls Plantation (Mouer and Kiser 1993). Certainly I

owe a considerable debt to all my colleagues who have devoted so much time to

digging and interpreting 17th-century Virginia. A few outstanding works require

special mention: William Kelso’s (1984) Kingsmill Plantations, Ivor Noel Hume’s

(1979) Martin’s Hundred, and James Deetz’s (1993) Flowerdew Hundred.

Thomas Harris is someone we know primarily from official

documents, which reveal quite a bit, because he left a pretty good paper trail

thanks to his various land dealings and military activities. Still, much

remains unknown about Thomas Harris, although genealogists have contributed

considerably to the facts–as well as some fiction and confusion–surrounding

Harris’s life in England and Virginia. He and his two wives were officially

designated with the status “ancient planter” due to their having been in

Virginia during the tenure of Sir Thomas Dale. That gave him access to an

additional 150 acres of land over and above the 50-acre headrights they each

earned for themselves, and any additional headrights for servants imported to

the colony.

We know that Dale assigned Harris Lieutenant of Digges’s

Hundred, and that he was living on the “Neck of Land” during the 1622 massacre.

His patents place him at Curles Neck by 1630, the

year that many who had moved into Jamestown or one of the large fortified

villages erected after the massacre returned to earlier habitations. He held a

number of militia posts and commissions and was, for much of his adult life,

the senior military official in what was then known as “the upper parts” of the

colony. While the evidence isn’t conclusive, it appears he never owned slaves. He

was certainly one of the longest-lived of the “ancient planters” in Virginia.

While the historical literature on the 17th-century

Chesapeake is huge, and there is an especially good basis of recent scholarship

in social history and archaeology, there are few works that, on their own,

stimulate for me the “historical imagination” needed to reach into that distant

culture. One of the best such pieces, in my opinion, is still Morgan’s (1975)

American Slavery, American Freedom. While Morgan sketched out a broader thesis,

he drew on the emerging literature in archaeology and social history to elicit

at least some sense of everyday life.

Another work I have long admired is the Rutmans’

(1984) experiment in creating an evocative historical ethnography: A Place in

Time. The Rutmans draw a convincing picture of

colonial Middlesex County, but their account of this lower Tidewater area does

not square with what I have come to sense about the Fall-Line frontier up

river. Many years of archaeological work have driven home to me the fact that

the Fall Line was different from the tobacco-raising heartland of the early

colony in many important ways. Throughout the 17th century this area was the

center of the Indian trade. Many of the settlers here were not typical English planters;

there were also French sheepherders and Irish millers. They depended on

industry, commerce or military positions as much as or more than they did on

agriculture. Servants were as likely to include Native Americans as Africans or

English. Cultural and economic interactions among colonists and Indians were

far greater here, and when wars and skirmishes broke out they were likely to be

within these precincts. It was in Henrico County that Bacon’s Rebellion was

fomented. It was in this cauldron of peripheral “multiculturalism” that many of

the important historical events and cultural developments of early Virginia

were centered. This intensive variety and interaction created creolized

cultural forms which I have discussed at some length elsewhere (Mouer 1987, 1993a, in press).

William Harris, the narrator of the story, was probably as

typical as anyone in these parts in the later 17th century, which means he was

neither extraordinarily rich, nor poor; neither very powerful, nor by any means

without his own sphere of influence (Figure 3). The son of an “ancient

planter,” he had a small tobacco farm that was worked by his family and,

occasionally, one or two servants. So far as I can

tell, like most second-generation Virginians, he probably never saw England. He

was a creole colonial. He was a landowner, but his holdings were modest. He

rose to the rank of major as second-in-command of the combined militias of

Charles City and Henrico Counties. He was what I once called a “local elite:”

one of the peasantry living in the colonial periphery that rose to a modicum of

local power, but whose wealth and influence did not extend to the colonial

core, nor were they nearly as great as the colony’s core elites (Mouer 1987).

In 1670 he ventured west beyond the Fall Line with a troop

of mounted rangers accompanying John Lederer (1966

[1671]), a Swiss explorer with a governor’s commission. His fear of Indians and

of going beyond what had been the boundary of the Virginia colony for 70-some

years led him into a conflict with Lederer. He

finally abandoned the explorer just 50 miles from the Fall Line and returned

home with his troop and announced that Lederer had

been killed by Indians. A year later, John Lederer

returned to Virginia having mapped and documented his travels throughout a huge

section of the American Southeast. Harris was shamed. For reasons that aren’t

entirely clear, he died impoverished. His probate inventory include a lump of

melted pewter, a bedstead, and an old mare considered to have no value.

My principal documentary and secondary sources for William

Harris’s era are those dealing with Bacon’s Rebellion. The central published

works include Wertenbacker (1940), Washburn (1957),

and Webb (1984), as well as a very useful and extensive compilation of documents

and abstracts concerning the rebellion compiled by Neville (1976). We have few

primary sources for Curles Plantation in this period

other than deeds, wills, and some other court papers. The cream of the crop is

an extensive room-by-room inventory made under the commissioners sent to

investigate the rebellion (Anon. 1677). They charged surveyors to inventory

rebels’ plantations that had been seized by Governor William Berkeley. From

this document we get a very good picture of the estate as it existed right at

the end of the rebellion in May of 1677, including a detailed list of Bacon’s

Indian, Black, and European servants.

I chose Harris, and his story about his father’s life,

because I wanted to present a chronicle of events at Curles

that could embrace more than a single lifespan. William Harris lived through

the period of the 17th-century occupation at Curles,

and he is a credible first-hand observer of events on, and surrounding, the

plantation. I wanted to contrast the physical world the Harris’s built at Curles with what we have come to know about the preceding

period of the 1610s and 1620s, and William Harris was a subject who might have

had reliable second-hand knowledge of that time from his father.

I chose the device of a written document primarily because

we have very few sources that permit us to infer the speaking manner of a

frontier-dwelling, native-born Virginian of the later 17th century. We have

writings of men like Nathaniel Bacon and William Bird, but these were much more

powerful elites, raised and educated in England, whose lives revolved around

Jamestown and London, despite their geographic locations at the Falls of the James. What we do have in plenty are petitions,

court papers, etc. Their language is conventional, somewhat formal, and

immediately familiar to any who have spent much time reading papers of the

period. By “reading” a fictitious “document,” I avoided having to act out a

character whose clothing and language I can scarcely imagine. For the written

version presented here, the reader’s suspension of disbelief is aided by the

use of approximations of 17th-century spelling, orthography, capitalization,

abbreviation, and all the usual inconsistencies in each of these found in

period documents.

References Cited

Anonymous

1677 An Account of the Estate of Nathaniel Bacon, Jr., Dec’d. C.O.5/1371, Pt.II,

227vo-230, May 11, 1677. Colonial Records, London.

Deetz, James

1993. Flowerdew Hundred: The Archaeology of a Virginia

Plantation, 1619-1864. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia.

Kelso, William M.

1984 Kingsmill Plantations, 1619-1800: Archaeology of

Country Life in Colonial Virginia. Academic Press.

Lederer, John

1966 [1671] The Discoveries of

John Lederer. Readex

Microprint.

McLearen,

Douglas C., and L. Daniel Mouer

1993 Jordan’s Journey, Volume II: Report on the 1992

Excavations at Archaeological Sites 44PG302, 44PG303, and 44PG307. Report

prepared by VCU Archaeological Research Center for The Virginia Department of

Historic Resources and The National Geographic Society.

1994 Jordan’s Journey, Volume III: Report on the 1992-1993

Excavations at Archaeological Site 44PG307. Report prepared by VCU

Archaeological Research Center for The Virginia Department of Historic

Resources and The National Geographic Society.

Morgan, Edmund S.

1975 American Slavery, American Freedom: The Ordeal of

Colonial Virginia. W. W. Norton and Co., New York.

Mouer, L. Daniel

1998 Digging Sites and telling Stories: Essays in

Interpretive Historical Archaeology. Studies in Global Historical Archaeology

series, edited by Charles Orser. Plenum Publishing,

New York.

1994 “…we are not the veriest

beggars in the world:” The People of Jordan’s Journey. Presented at the Annual

Conference on Historical and Underwater Archaeology, Vancouver, B.C.

1993a Chesapeake Creoles: An Approach to Colonial Folk

Culture. In The Archaeology of Seventeenth-Century Virginia, edited by Dennis

J. Pogue and Carter Hudgins. Special Publication of the Archaeological Society

of Virginia, Richmond, pp.

1993b An Update on the Curles

Plantation and Jordan’s Journey Projects. Jamestown Archaeology Conference,

Jamestown.

1993c Telling Stories About Rocketts: Community and Diversity on Richmond’s Early

Waterfront. Paper presented at the Conference on Historical and Underwater Archaeology,

Kansas City.

1992a Curles, Rocketts,

and Jordan’s Journey: A progress report on three major excavations. Paper

presented to the Jamestown Archaeology Conference, Fredericksburg.

1992b Rocketts: The Archaeology

of the Rocketts #1 Site, Technical Report. Report in

3 volumes prepared by the VCU Archaeological Research Center for the Virginia

Department of Transportation.

1991a Digging a Rebel’s Homestead: Nathaniel Bacon’s

fortified plantation called “Curles” Archaeology

magazine, July/August, pp: 54-57.

1991b Three Centuries on the James: Archaeology at Rocketts, Curles, and Jordan’s

Journey. Paper presented to the Annual Meeting of the Archaeological Society of

Virginia, Roanoke.

1991c Jordan’s Journey and Curles:

the 1991 Season’s Finds. Paper presented at the

Jamestown Archaeology Conference, Washington’s Birthplace National Landmark.

1990a Progress Reports: Jordan’s Journey, Rocketts Port, and Curles

Plantation Excavations. Paper presented at the Jamestown Archaeology Fall

Conference.

1990b “An Ancient Seat Called Curles”:

The Archaeology of a James River Plantation: 1984-1989. Paper presented to the

Conference on Historical and Underwater Archaeology, Tucson.

1989a The Rebel and the

Renaissance: Nathaniel Bacon at Curles Plantation.

Paper delivered to the Middle Atlantic Archaeology Conference, Rehobeth Beach, Delaware.

1989b The Curles Plantation

Project at the Five Year Mark: Retrospect and Prospect. Paper delivered to the

Jamestown Archaeology Conference, Jamestown.

1988a The Excavation of Nathaniel Bacon’s Curles Plantation. In The Henrico County Historical Society

Magazine, Vol. 12, pp: 3-20.

1988b Nathaniel Bacon’s Brick House and Associated

Structures, Curles Plantation, Henrico County,

Virginia. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the Archaeological Society

of Virginia, Hampton.

1987 Everything in Its Place: Locational Models and

Distributions of Elites in Colonial Virginia. Paper delivered at the annual

meeting of the Society for Historical Archaeology, Savannah, Georgia.

1985 What are you looking for? What have you found? What

will you do with it now? Paper presented at the Jamestown Archaeological

Conference, sponsored by the Association for the Preservation of Virginia

Antiquities, Jamestown.

Mouer, L. Daniel, and R.

Taft Kiser

1993 Falls Plantation and the Confederate Navy Yard: An

Archaeological Assessment of Richmond’s Eastern Waterfront. Report prepared by

VCU Archaeological Research Center for the William Byrd Branch, Association for

the Preservation of Virginia Antiquities.

Mouer, L. Daniel, and

Douglas C. McLearen

1991 “Jordan’s Journey”: an Interim Report on the

Excavation of a Protohistoric Indian and Early 17th Century Colonial Occupation

in Prince George County, Virginia. Report prepared by VCU Archaeological

Research Center for the Virginia Department of Historic Resources.

1992 Jordan’s Journey: A Report on Archaeology at Site

44Pg302, Prince George County, Virginia, 1990-1991. Report prepared by VCU

Archaeological Research Center for The Virginia Department of Historic Resources

and The National Geographic Society.

Mouer, L. Daniel, Jill C.

Wooley, and Frederic W. Gleach

1986 Town and Country in the Curles

of the James: Geographic and Social Place in the Evolution of James River

Society. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the Middle Atlantic

Archaeological Conference, Rehobeth Beach, Delaware.

Neville, John Davenport

1976 Bacon’s Rebellion: Abstracts of Materials in the

Colonial Records Project. The Jamestown Foundation.

Noël Hume, Ivor

1979Martin’s Hundred. Alfred Knopf, New York.

Rutman, Darrett B., and Anita H. Rutman

1984 A Place in Time: Middlesex County, Virginia,

1650-1750. Norton, New York.

Washburn, Wilcomb

1957The Governor and the Rebel. University of North

Carolina Press, Chapel Hill.

Webb, Stephen Saunders

1984 1676: The End of American Independence. Harvard

University Press, Cambridge.

Wert

1940Torchbearer of the Revolution: The Story of Bacon’s

Rebellion and its Leader. Princeton University Press, Princeton.

--------------------------------------- End of Dan Mouer’s

presentation

________________________________________________________________________________________________

Maj.

William Harris and Col. Francis Eppes were in command

of the Indian Battle of 1678

Major William Harris (b ca 1629 Henrico Co., Va., died 1678

Va).

He was killed in a battle with Indians near the present

town of Richmond, Va. The battle was between the

Militia and a band of Indians raiding from the north. Colonel Francis Epps and

Major William Harris were both killed.

A letter of Colonel Herbert Jeffreys,

the Governor of Virginia, to Sir Henry Coventry reported that: "On the

22nd and 23rd of August [1678] some Indians came downe

uppon james River to the

number of 150 or 200 in Henrico County on the 24th some of the Militia officers

of Henrico County gott upp

a party of forty six horse and marched imediately upp to [ ] upper plantation of Coll:

[Rowland] Places: The cheife officer Coll: [Francis] Epps and Major [William] Harris were killed

and two more wounded Indians Kill Maj. William Harris (1678).

In 1678 Maj. William Harris and Col. Francis Epes were in command of a militia of hands near present-day

Richmond when an Indian raiding party came from the North. A letter from John

Banister of 6 April 1679 described the events.

... Last Summer

they made several Incursions among the Inhabitants on the Heads of Rapahannock, York & Our (i.e.) James River destroying

their cattle, rifling their houses, & killing and carrying away some

Families. But tho' we were sufferers in our Stocks

& Cropps, & some of the loss of household

goods also, & (blessed be God) none of us lost our lives. One Coll[.] Epes indeed was killed who with some Forces rais'd in Our (i.e.) Henrico

County, came in pursuit of them two days after the mischief was done. They

found them Shut up in a Corn field belonging to the Upper Plantations on the

North-side of ye River, & had they been but half so courageous as they were

cautios might have cut them all off together.But while one durst not shoot nor the other for

want of extent of Commission & for fear of breach of Peacd,

out get the Indians, gain the clear'd ground &

fire on them. The Coll. paid dear for his deliberation, he was shot in the

throat by an Indian at least 200 paces distant. We lost another stout man at

the same time, one Major Harris, who rashly pursuing the flying Enemy with a

Pistol only in his hand & that too discharg'd was

shot and died a Martyr to his foolhardiness. The Indian that shot him was kill'd & one woman taken prisoner, ye rest escap'd over the River...

Colonel

Francis Eppes II

Francis Eppes II was the son of

Francis Eppes I, "the Immigrant," and wife

Mary. He was born c. 1627 in Virginia. His father returned to England c.1629,

taking Mary and two small sons with him, to tend to the affairs of John Eppes, recently deceased. The third son, Thomas, was born

in 1630 in London. When the family returned to Virginia, the senior Francis Eppes was able to claim headrights for his wife and three

children by paying for their passages.

Francis Eppes II served as

justice of the Charles City County monthly court. He served in the Virginia

Militia, rising to the rank of captain by 1660 and to Lt. Col during Bacon's

Rebellion. He moved to Henrico County, Virginia c.1665 and served as a justice

in that county, as well. He served in the House of Burgesses.

Francis married twice. The first wife's name is not known.

It has been suggested that her birth name was Wells or Welles, but no documents

have been found to support this name. There was one child from this marriage.

His second wife was Elizabeth Littlebury, widow of

William Worsham. There were four children from this

marriage.

Francis died in August, 1678, of a wound, possibly from

fighting Indians. He had made a deposition earlier that year reciting he was 50

years of age. From this we can estimate his date of birth.

Before his death he made a nuncupative {"oral"}

will dividing his estate, and designating his son Francis executor, to which

will William Randolph and Richard Cocke, Sr. were

witnesses. On December 2, 1678 Richard Cocke, Sr.,

aged about 38, deposed that he was at the house of Colonel Francis Eppes the day before he died, and Col. Eppes

said he wished his estate divided equally between his wife and four children.

And on the same day Wm Randolph, aged about 28, deposed that he was at the

house of Col. Francis Eppes a few days before he

died, and said Eppes, being dangerously wounded,

called him, and desired him to take notice that he wished his estate to be

equally divided between his wife and four children, and when his wife asked

about his land, he said and that Lanton would serve

one of the boys. His son Francis was his administrator and among his accounts

with the estate are payments to Parson Williams and Parson Ball, doubtless for

the funeral services.

During his lifetime he carried on a mercantile business at

Bermuda Hundred, and was agent for a London firm.

Child of Francis Eppes II and

first wife:

Frances Eppes III, b. 1657

Children of Francis Eppes II and

wife Elizabeth Littlebury:

William Eppes, b. 1662

Littlebury Eppes

Mary Eppes, b. 1664

Anne Eppes.

Eppes Family - Francis Eppes

I

Lt. Colonel Francis Eppes I

(1597-1674) (called Captain Eppes elsewhere) obtained

a grant of land August 26, 1636, for transportation of himself, his three sons

and some 30 servants into the Virginia Colony, and in 1635 settled there on the

south shore of the James River near the mouth of the Appomattox. this river formed the boundary line between the southern

halves of the counties of Henrico and Charles City, which then lay on both

sides of the James River; and as Colonel Eppes

subsequently acquire very extensive estates in both counties he was returned to

the House of Burgesses indifferently from either. Sometime previous to his

death which occurred in 1655 he became a member of the Colonial Council. Four

of his descendants in lineal succession, each bearing the name Francis and

three of them distinguished by the title of Colonel, all county officials and Member

of the House of Burgesses, enjoyed in tail(?) male(?) the large landed estates

the first Francis had secure in that part of the County of Henrico which was

subsequently made Chesterfield. The lands in and around City Point (Appomattox

Manor) which were granted in 1636 are still owned by the Eppes

family; it is said that no other tract of land in America has been so long in

unbroken possession of one family. Francis Eppes I

was Lt. Colonel of the County, member of the House of Burgesses 1625-1632, Commissioner

1631-39, Member of the Council April 30, 1652.

Appomattox

Manor

https://www.nps.gov/articles/appom.htm

____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________-

Curles Neck Plantation

Curles Neck

Farm is a large plantation style farm located on the northern banks of the

James River. It was first owned by

Captain Thomas Harris in 1635. He served

as a burgess (or representative) for this area in the House of Burgesses at

Jamestown.

William Harris fell heir to "Longfield",

later known as "Curles." His inheritance of

the plantation is established through a Henrico County record in a suit

entitled John Broadnax vs. Willm. Soane, entered 1

October 1700, to clear the title to the land and establish boundaries.

On 17 March 1664/5, William Harris sold Curles

to Roger Green, a merchant. A portion of Curles, the

Harris plantation, consisted of 820 acres originally patented by Thomas Harris

in 1638. Roger Green sold this portion of the estate to Thomas Ballard in

September 1668. Neither Green nor Ballard lived at Curles.

Thomas Ballard was a member of Virginia’s prestigious Governors Council. On 28

August 1674, Ballard sold Curles to Nathaniel Bacon.

Nathaniel had just arrived in Virginia with 1,800 in his pocket. With him was

his wife, Elizabeth, a relation of Royall Governor William Berkeley. They

immediately appointed him a member of the Governors

Council and granted him a license to participate in the lucrative Indian trade

monopoly. Nathaniel built his home at Curles and

maybe he took advantage of some structures put up by Capt. Thomas Harris.

Nathaniel was upset with the governor of Virginia for being

too friendly towards the American Indians and led Bacon’s Rebellion in

1676. His land at Curles

Neck was confiscated (taken away) and resold to the well-known Randolph family

(whose descendants were Thomas Jefferson and Robert E. Lee). The Randolph

family grew tobacco and built a large mansion on the property which fell into

disrepair after the Civil War. In 1894

an enterprising farmer named Charles Sneff purchased

the land. He started raising cattle,

sheep, and horses, and he built the mansion which is there today. After his death in 1913, a horse-lover named

CK Billings acquired the property and opened a horse racing track. The Strawberry Hill Horse Races were held

here during this time. The next owner,

AB Ruddick, started the famous Curles Neck Dairy farm

here in 1933 which was one of the largest dairy farms in the area. The milk was processed and bottled at a

factory in Richmond which still exists and is called the Dairy Bar.

By the mid

20th century Curles Neck Farm under the ownership

of Fred Watkins who purchased the property in 1943 had become one of the

largest dairy suppliers in the eastern United States.

Curles Neck

is no longer a dairy farm and is being mined for sand and gravel.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Curles_Neck_Plantation

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bermuda_Hundred,_Virginia

Other

Ancestors in the area who were contemporaries of the Harris and Eppes families.

In 1661 the clerk of Charles City County, Virginia recorded

the following in his official report. Governor ffrancis

Moryson is appointing Coll. Abram Wood, L t. Coll.

Thomas Dewe, Major William Harris, Captain John Eppes, Captain William ffarar,

Peter Jones, Captain Edd Hill Junr.

and Captain ffrancis Grey to

be Commanders of the Regiment of the trayned bands in

the Counties of Henrico and Charles City. The Majors companie

to be from Powells Creek in Henrico Coun. to the falls of James River

on the South side & hence of and Curles

plantation to four mile Creeke. .Major William Harris

& Capt. William ffarrar of Henrico Militia are to

give & present an accot of their proceedings in

all the places under their bands (together with the general lists) will all

possible speed to Coll Abraham Wood Esq . att ffort Henry, and to be very

wary and circumspect that no ammunition be spent or waste at the said musters

but only false fires to be given to prove readiness of their guns.

Notes: Captain William ffarar was

Capt. William Farrar, and Captain Peter Jones, after a later promotion, was

Maj. Peter Jones I, the father of Capt. Peter Jones II who married Mary Batte.

In 1678, Major William Harris and Colonel Francis Epes were in command of a militia of "trayned hands" near present-day Richmond when an

Indian raiding party came from the North. A letter from John Banister of April

6, 1679 described the events.

...Last Summer they made several Incursions among the

Inhabitants on the Heads of Rapahannock, York &

Our (i.e.) James River destroying their cattle, rifling their houses, &

killing and carrying away some Families. But tho' we

were sufferers in our Stocks & Cropps, & some

of the loss of house hold goods also, & (blessed be God) none of us lost

our lives. One Coll Epes

indeed was killed who with some Forces rais'd in Our (i.e.) Henrico County, came in pursuit of them two days

after the mischief was done. They found them Shut up in a Cornfield belonging

to the Upper Plantations on the North-side of ye

River, & had they been but half so courageous as they were cautios might have cut them all off together. But while one

durst not shoot nor the other for want of extent of Commission & for fear

of breach of Peacd, out get the Indians, gain the clear'd ground & fire on them. The Coll. paid dear for

his deliberation, he was shot in the throat by an Indian at least 200 paces

distant. We lost another stout man at the same time, one Major Harris, who

rashly pursuing the flying Enemy with a Pistol only in his hand & that too discharg'd was shot and died a Martyr to his foolhardiness.

The Indian that shot him was kill'd & one woman

taken prisoner, ye rest escap'd over the River...

The paragraphs above are listed to show the families of my

ancestry and their future intermarriages.

Col. Abraham Wood was the employer of Nicholas Overby

(Overbury) the immigrant, on my maternal line, my 8th

Great-Grandfather https://edavidarthur.tripod.com/NicholasOverbyImmigrant.pdf

who was in this area at the same time as Francis Epps II and William Harris.

Later Jeremiah Overby,

great-grandson of Nicholas, married Ann Cousins, great-granddaughter of William

Harris. Jeremiah Overby’s son John married Charlotte Eppes, great-great-granddaughter of Francis Eppes II.

Also, Abraham Wood’s son-in-law, Peter Jones is my 9th

Great-Grandfather on my paternal line. Another ancestor on my paternal line who

was in the area as a contemporary was my 8th Great-Grandfather John

Ellis https://edavidarthur.tripod.com/JohnEllis/JohnEllisFamily.htm

. Also employed by Abraham Wood was cousin Gabriel

Arthur https://edavidarthur.tripod.com/GabrielArthur/GabrielArthur.htm

.

Download a pdf file of this webpage at

https://edavidarthur.tripod.com/ThomasEHarris.pdf